| |

|

Introduction.

|

|||

The We have attempted to present this page as an impartial account of historical events as they unfolded in Ireland. Our sources were many and often presented conflicting accounts, as of course is only to be expected. It is difficult for authors to avoid applying his or her own personal political and religious allegiance to the interpretation of events and situations they are describing. Not forgetting also that the original source material from which history is compiled is usually written, sanitized and often embellished by the victor, to the detriment of the vanquished and the truth. |

|||

|

|

The

Provinces. |

||

| The

original provinces, sometimes called the five fifths The Coming of Christianity.(431-795) In 431, Pope Celestine sent Palladius as first

bishop to the Irish, Pallidus died shortly after arriving in Ireland.

He was replaced by Patrick

who landed in Ireland in 432, he become the patron saint of Ireland.

Patrick was a native of According to tradition in 432, Patrick landed at the mouth of the Slaney river which flows into Strangford Lough near Saul, in County Down, he made contact with the local chieftain Diohu who after a conversation with Patrick gave him his barn the Irish word for barn was sabhall, Patrick converted it and so it became his first church in Ireland. Later he was called before the high king, Laoghaire, at Tara, Laoghaire was impressed with Patrick and he gave him permission to preach. For thirty years he traveled the country, founding churches and ordaining priests. He died in 461 and was buried at Downpatrick County Down which had become the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland. Modern scholars dispute this traditional account of St. Patrick's life and argue that a number of missionaries converted the Irish to Christianity, indeed it seems entirely possible that small pockets of Christianity already existed brought to the island by traders. Some scholars are of the opinion that the Patrick story was invented entirely by the Catholic church, but all scholars agree that the people eventually accepted the new religion without much opposition. The early church in Ireland incorporated many of the Pagan ceremonies and rituals into their services and church calendar. It has been suggested that some of the early monastic sites occupied land previously used as Druidic colleges and may have taken over from them. Certainly early church sites tended to be sited in or near oak groves, the oak was sacred to the Celts. This policy was eminently successful in making converts, and may have been one reasons which led the Irish church into conflict with Rome, the dating of Easter was a particularly contentious issue which was not settled until 703. St. Patrick and other missionaries divided the country into dioceses and put a bishop in charge of each of them. In the years that followed, many monasteries were founded throughout the country. Gradually, monasteries became an important feature of Christian life in Ireland. The chief founders of Irish monasteries were St. Enda of the Aran Islands, St. Finnian of Clonard, St. Columba of Derry and Kells, who is also called Columcille, St. Brendan of Clonfert, St. Brigid of Kildare, St. Comgall of Bangor, St. Finbarr of Cork, and St. Kieran of Clonmacnoise. The monasteries became so important that the system of dioceses founded by St. Patrick broke down. Each monastery was independent, and the abbots of the monasteries eventually became more powerful than the bishops. |

||

|

|

The

Dark Ages. (500 to 800) AD |

||

| During this period generally called the Dark Ages in Europe religion and scholarship almost disappeared in some other countries. But during this time, Ireland became a great center of education and scholarship. Many students came from Britain and Europe to Ireland to study in its famous monastic schools. At least two kings from overseas were educated in Ireland: Dagobert II, King of the Western Franks, who's citadel of Rennes le Chateau, central in the mystery of the Holy Grail, the Knights Templar and Mary Magdalene, popularized in the thriller by Dan Brown in the Da Vinci Code, and Aldfrid of Northumbria was another. Scripture and theology were the chief subjects of study at these schools. |

||

|

|

The

Monasteries. |

||

| The

Irish monks believed that the greatest sacrifice they could make was to

go into exile "for the love of Christ." St. Columba of Derry

was one of the first In time, a decline in the religious fervor of the monks set in. Some monasteries passed into the control of lay people, and many kinds of abuses resulted. In the 700's, a reform movement began, led by men called Celi De (servants of God), who preached a return to the former strictness of monastic life. But, before they could achieve much, bands of warriors from Scandinavia, called Vikings, began to raid the country. Long before the coming of the Vikings Irish kings and chieftains had become notorious for their depredations of ecclesiastical properties. The greatest of the Irish raiders was Feidlimid mac Crimthainn, king of Munster, who is reputed to have burned the monasteries of Kildare, Clonfert, Durrow, and Clonmacnoise among others. Feidlimid was himself in holy orders, probably of Episcopal rank As such sympathies lay with the Celi De, and justified his raids as a crusade to stamp out corruption in the church. Although his victims were probably chosen because of their affiliation with the Ui Neill kings of the north. The Arts. The arts owed much to the monasteries. Some of

the finest metalwork |

||

|

|

Rival

Irish Kings (950-1169)

|

||

| The Battle of Clontarf. The struggle for power among provincial kings went on, in spite of the Viking invasions. By the end of the 900's, Brian Boru, the king of a small state in Clare called Dal Cais, had conquered his greater neighbours and made himself the strongest king in the southern half of Ireland. Brian Boru had set aside his troublesome wife Gormlaith, a 'bartered' princess of Leinster. By an earlier marriage she was mother to Sitric Silkbeard, King of Viking Dublin. The name Boru is a shortened version of Brian Boroimhe, meaning Brian of the tributes referring to his tendency to exact tributes by taking hostages from defeated enemies, this was a practice in which most rulers of the time engaged. Gormlaith, and her brother Maelmora, encouraged Sitric to rally their Viking allies from Scandinavia and overthrow the powerful Boru, thus completing their conquest of Ireland. Maelmora made an alliance with Sitric, who got help from the Vikings of the Orkney Islands and the Isle of Man. Boru, in the meantime, sent word to his allies in Ireland, both his Viking allies and the great Gaelic clans. Amongst those who responded were the O' Kellys of Uí Maine who, under their chieftain Tadhg Mór O' Kelly, marched to Clontarf to side with Boru. The powerful O' Kelly chieftain and his army were the only Connacht chieftain to rally with Boru. A great battle was fought at Clontarf, near Dublin, on Good Friday, 1014. It ended in victory for Brian's army, at this time he was an old man, prior to the battle he addressed his assembled troops with great eloquence, exhorting them to fight for their freedom and rid their country of foreign repression, Brian himself was killed after the battle by fleeing Vikings who came upon his tent by chance. Brian's remains were conveyed to Armagh. With Brian, some accounts say, went also the bodies of Murrough (Brian's son), Conaing, and Moltha. The body of Brian was deposited in a stone coffin on the north side of the high altar in the great cathedral, the body of Murrough, it is said, being interred on the south side of the church. Other sources

report that Prince Murrough was buried in the west end of a chapel in

the cemetery of Kilmainham. Over his remains was placed a stone cross

on which his name was engraved. It is said that this cross fell from its

pedestal in 1798. Under the base were found Danish coins and a sword in

a good state of preservation, supposed to be that which the prince Murrough

used at the battle of Clontarf. Brian's pre

battle speech. |

||

|

|

After

Brian Boru. |

||

| For a hundred years after the death of Brian, rulers of powerful provincial kingdoms fought, bitterly for supremacy. But none of them had any lasting success. In 1106, Turlough O'Connor became king of Connacht. He was a skillful warrior. He strengthened his kingdom by building fortresses in it. He built bridges over the River Shannon, so that he could attack the other provinces swiftly, and he made great use of fleets in his wars. He tried to weaken his rivals by dividing their kingdoms. He partitioned Munster and Meath among a number of petty kings. For a time, he was the most powerful king in Ireland. |

||

|

|

The

Synod of Kells in 1152 |

||

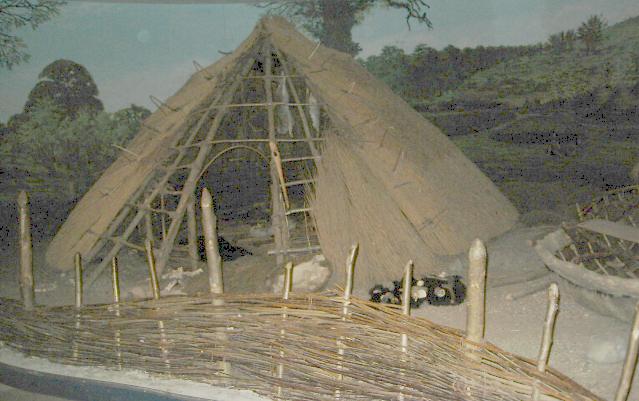

| The period after the Viking invasion was a time of recovery for religion and culture, in spite of the disturbed political life of the country. The Irish Church was reformed and reorganized into dioceses. At the Synod of Kells in 1152, the country was divided into 36 dioceses, and grouped into 4 provinces under the archbishops of Armagh, Dublin, Cashel, and Tuam. St. Malachy of Armagh was the greatest of the religious reformers and introduced the Cistercian Order into Ireland. In 1142, the first Irish Cistercian monastery Mellifont Abbey was founded in County Louth. Many of Bishops Seats where hereditary between 1000 and 1100's, the economy of the country was mainly pastoral. A person's wealth was reckoned by the number of cattle he or she owned. The social unit was still the Tuath, which was based on family groups. The ruler of a Tuath lived in a fortified house called a rath, or dun, together with a brehon (lawyer), minstrel, physician, and several craft-workers. The ruler's subjects lived in huts of wattle and clay. The people were poorly armed and no match for the warlike Normans who invaded Ireland in the latter part of the 1100's. Between November 1155 and 1156, John of Salisbury a friend of Theobald of Canterbury, Thomas Beckett, and Bernard of Clairvaux, spent three months with Pope Adrian IV (Nicholas Breakspear, the only English Pope) and persuade the Pope to issue the 'Bull Laudabiliter' which gave full Papal approval for the Anglo Norman invasion of Ireland. Nicholas Breakspear at Answers.com In 1153 Dermot McMurrough, king of Leinster attacked the lands of Tiernan O'Rourke, king of Breifne (Leitrim Cavan area) he carried off large numbers of livestock, as well as O'Rourke's wife Dervorgilla, opinions differ as to whether or not she went willingly, however she was eventually returned. In 1156 Turlough O'Connor king of Connacht died, Murtagh MacLoughlin, king of Ulster, with the help of Dermot McMurrough, king of Leinster, made himself king of Ireland. Ten years later, he was overthrown, and Turlough's son, Rory O'Connor, became the one who was to be the last native king of Ireland. Eventually in 1166 MacMurrough was expelled from Ireland by Roderick (Rory O'Connor) high king of Ireland. MacMurrough went to England where he sought help from King Henry II. Henry eagerly seized the opportunity of expanding his kingdom and gave gave him permission to enlist several Anglo Norman Lords, the chief of which was Richard FitzGilbert de Clare (Strongbow) MacMurrough promised his daughter Aoife's hand in marriage to Strongbow as well as succession to his kingship of Leinster. |

||

|

|

Events

leading up to |

||

| The

Norman Invasion of Ireland. The Normans were descended from Vikings who had

been granted a large province in northern France in the 900's, on condition

that they ceased to raid the rest of the country, this area came to

be known as Normandy. In 1066, its ruler, William Duke of Normandy,

claimed the throne of England, he crossed the English Channel The previous year 1065 Harold Godwinson succeeded Edward the Confessor to the throne of England, Harold's brother Tostig, Duke of Northumberland desired the throne for himself, he mounted an unsuccessful insurrection against Harold which led to his banishment. Tostig made his way to Norway and enlisted the

help of the Norwegian King Harold Hardrada, a Two days later on the 27th William Duke of Normandy set sail for England with his army, they managed to evade the English fleet in the channel, landing at Pevnsy on the 28th.September. Harold learned of William's invasion on 1st of October, on the 3rd he and his army embarked on an eight day forced march south. The two army's meeting at Hastings on the 14th the battle that ensued cost Harold his country and his life, it is said shot in the eye by a arrow. |

||

|

|

| By around the 1300 the Normans controlled most of the country. But they did not succeed in conquering Ireland as they had conquered England. Ireland had no central government which they could take control of. The Normans were not a united group. The various barons vied with each other to enrich themselves and fought not only with the Irish but among themselves. This continuous warfare gradually reduced their strength, and they were not replaced by fresh settlers. Those in remote areas of the country began to adopt the language and customs of their Irish neighbours. Some Norman families adopted Irish name forms. The De Burgh family took the name Burke; the Barry family, MacAdam; and the Staunton family, McEvilly. |

||

|

|

The

Bruce's in Ireland. |

||

| Anglo-Norman power in Ireland began to fade in Ireland, more and more of the country fell back into the hands of the Gaels. Donnell O'Neill king of Tir-Owen and some of the other Lords impatient to see the end of Norman rule, invited Edward Bruce to Ireland in 1315, this perhaps was a little ironic as the Bruce's were themselves of Norman decent. Their ancestor Robert de Brusse of Cherbourg came to England with William the Conqueror in 1066 his son Robert (1078- 1141) was a companion in arms of King David I of Scotland from whom he received a grant of the lordship of Annandale in Dumfriese and Galloway. In

1315 the English although outnumbering the Scots by three to one were

defeated by Battle of Bannochburn at Answers.com After Bannochburn Edward, Earl of Galloway, had thousands of soldiers at his disposal, bolstered by his recent successes, and encouraged by Robert, who perhaps fearful of Edwards fierce ambition seen a campaign in Ireland led by Edward as a means of extending the families power, and averting a power struggle between the two in the future. On May 25th 1315 Edward landed a force of some six thousand men at Larne in county Antrim. These men were mail clad battle hardened veterans, they were soon joined by large numbers of Irish infantry. This Scottish-Irish alliance proved to be almost invincible, proceeding from victory to victory. They defeated Hugh de Lacys and Hugh de Montford at Kells and won many other battles further south. One prize that eluded them was Carrickfergus castle which was still in the hands of the English. At the outset Edward left a portion of his army to lay siege to the castle. During Easter 1316 Sir Thomas de Mandeville attempting to relieve the castle by an approach from the sea was defeated and killed. After about a year on 1st May 1316 Edward crowned himself king of Ireland at Dundalk. By September that year when he was joined by his brother Robert, most of northern portion of Ireland was under his control, September of that year saw the surrender of Carrickfergus. The two brothers took most of the midlands, but Dublin eluded them, mainly because as was the case in Carrickfergus, they lacked siege engines. Their conquest and pillage of the country to sustain their army's, led inevitably to famine. In 1317 Robert went north to Ulster and from thence to Scotland to attend to his business, promising to send men and supplies. By 1318 most of the island was in the grip of famine, one notable battle took place near Ennis county Clare, in the battle of Disert O'Dea the O'Brien's regained their kingship. The tide of good fortune was about to turn against Edward, in the late summer of 1318 a superior force led by John de Birmingham was marching against him. The two armies met on 14th October 1318 at Faughart near Dundalk county Louth, Edward was killed and his army defeated, the remnants of Edward's army returned home as best they could. His Irish allies suffered greatly after the defeat. A chronicler wrote of Bruce at the time |

||

|

|

Mary

Tudor. |

||

| In 1547 Henry died and was succeeded by the boy King Edward VI. England was ruled by the nobility until 1553 when Queen Mary came to the throne. Mary pardoned O' Conner and he returned to Ireland, The tower had obviously not quenched his desire to regain his lost lands, No sooner was O'Connor back in his home territories than he once more had rebellion on his mind. He was again captured and imprisoned Mary reversed the previous

|

||

|

|

Queen

Elizabeth I. |

||

| Queen

Mary was a fervent Roman Catholic who worked hard to restore the old

religion in both England and Ireland. Her half-sister, Elizabeth, The arrangement made by Henry VIII did not endure. In 1559, when Conn O'Neill died, the men of Tyrone elected his son Shane to succeed him. Shane took the Irish title O'Neill, completely ignoring the English title, Earl of Tyrone. But Shane quarreled with his neighbours and was killed in a brawl in 1567. |

||

|

|

The

Munster Plantation |

||

| Elizabeth was concerned about the south of Ireland, because she feared that the Spanish might make a landing there. King Philip of Spain is reputed to have said "He who holds the key to Ireland also holds the key to England's door" In 1597, James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald, cousin of the Earl of Desmond, raised a revolt and appealed to the Pope and the king of Spain for help. Fitzgerald landed with a tiny band of mercenary soldiers in the pay of the Pope in July 1597 at Dun an Oir near Smerwick harbour in County Kerry. His effort failed and he was killed in a skirmish. The following year a large force of Spanish and Italian troops recruited by the Pope to assist the earl of Desmond, landed and established a fort at the same place. The English besieged the fort by sea and land, and the foreigners surrendered. The Lord deputy at the time Lord Grey delegated to Sir Walter Raleigh the task of massacring all six hundred of the defender. In an attempt to gain greater control of Ireland, Elizabeth decided to initiate a plantation of Munster. The Crown confiscated 202,000 hectares (500,000 Acres) from the Earl of Desmond and his followers. These lands were divided into estates varying in size from 1,620 (4,000 Acres) to 4,860 (12,000 Acres) hectares. They were given to English gentlemen, called undertakers, who undertook (promised) to plant them with English settlers. Among the undertakers were Sir Walter Raleigh and Edmund Spenser. But few English farmers could be persuaded to live in the Munster plantation, and consequently it failed. The greatest threat that Elizabeth had to face in Ireland was the combined revolt of Hugh O'Neill of Tyrone and Red Hugh O'Donnell of Tyrconnell in the 1590's. O'Neill, believing that Elizabeth aimed to conquer Ireland, built up an alliance of the Ulster chiefs to oppose her. War began in 1595, and in the early stages O'Neill won victories at Clontibret, in Monaghan, and at the Yellow Ford, in Armagh. |

||

|

|

The

Battle of Kinsale. |

||

| In 1600, Elizabeth made Lord Mountjoy (Charles Blount) Lord Deputy and Sir George Carew president of Munster. Mountjoy strengthened English garrisons in the north and embarked on a scorched earth policy they destroyed crops, murdered people including women and children and all farm animals . Meanwhile, Carew laid waste Munster and Sir Arthur Chichester Ulster. With this scorched earth policy they soon broke the power of the Irish chiefs who would have helped O'Neill. O'Neill's only hope lay in the arrival of foreign aid. A force of between 3,500 and 4,000 Spaniards landed on September 21, 1601 at Kinsale, in County Cork, they quickly set about fortifying the town against the English, the town of Kinsale is surrounded by high ground and not easily defensible from land attack, they were quickly besieged by Mountjoy. O'Neill arrived at the walls of the town in early December and surrounded the besiegers, but his plan for a coordinated attack on the English at dawn went awry when his forces were surprised and scattered by Mountjoy's cavalry. On December 24, 1601, the English won a decisive battle. The Spanish garrison was allowed to withdraw, but Mountjoy harried the Irish continually until O'Neill's finally surrender on March 30, 1603. During the war which became known as the 'Nine Year War' the great cruelty and treachery were practiced on both sides. The English adopted a scorched earth policy In order to destroy Irish resistance, they devastated villages, crops, and cattle, slaughtering many people not directly involved in the struggle. The greater part of Munster and Ulster was laid waste, more inhabitants died from hunger than from war. The Irish lost the war because the English systematically devastated large areas of Ireland depriving not only Irish soldiers but the Irish people of shelter and means of substance. The Irish were not as well equipped or supplied as the English, and because O'Neill did not succeed in building up a real national movement, this may have been because when he returned to Ireland in the service of England he took part in the suppression of the Desmond rebellion which may have made other Irish chieftains reluctant to place their entire trust in him. After the arrival of Mountjoy and Carew, O'Neill was confined to Ulster, short of food, and blockaded from the sea by the English navy. The Spanish came too late and landed too far away from the centre of Irish resistance in Ulster, no doubt the heavy loss of Spanish shipping on the west coast of Ireland at the time of The Armada 1588, (Estimated 25 ships) made them reluctant to make a winter passage up the west coast which would have been a lee shore to the prevailing winds. The defeat at Kinsale was a turning point in Irish history. It ended the power of the Irish chiefs and hastened the decline of the old Gaelic way of life. |

||

|

|

The

Flight of the Earls & |

||

| Subsequent

Plantation. After the defeat at Kinsale, and the subsequent surrender at Mellifont in 1603, Hugh O'Neill gave up his Irish title, O'Neill, and took the title Earl of Tyrone. He was allowed to retain most of the lands that had been granted to Conn O'Neill in 1542. Rory O'Donnell, younger brother of Red Hugh, became Earl of Tyrconnell on the same terms. The two Earls traveled to London, where the new king, James I, confirmed the Treaty of Mellifont. But the English officials who ruled Ulster were unfriendly and tried to turn the lord deputy in Dublin against the Earls. They spread a rumor that O'Neill and O'Donnell were planning another rebellion, and the Earls were summoned to London for questioning. Fearing for their safety, the Earls decided that the best course would be to leave the country and, in 1607, they sailed from Rathmullen on Lough Swilly County Donegal for the mainland of Europe. After the flight of the Earls, the government confiscated their lands and decided to plant six counties of Ulster, this became the basis for the subsequent Ulster Plantation. The last vestiges of an independence Irish parliament was destroyed by the creation of 40 boroughs out of small hamlets, a political maneuver that secured a permanent majority to the English Crown. When the new settlers arrived they found a barren uncultivated land, most of the native population were dead, killed in warfare although the majority probably died from starvation and exposure after their homes, crops, livestock and foodstores were destroyed. Armagh, Cavan, Derry, Donegal, Fermanagh, and Tyrone were planted with new settlers. The plantations of Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth I had not been successful, and the government planned the new settlement more carefully. It divided the land into estates of three sizes: 810 hectares (2000 acres), 607 hectares (1500 acres), and 405 hectares (1000 acres). Estates were granted to three kinds of people: English and Scottish settlers, who were not allowed to have Irish tenants; Servitors (men who had served in the English army in Ireland), who might take both British and Irish tenants; and Irishmen, who could have Irish tenants. Rents were low, but settlers were expected to build fortified houses. The City of London Companies received all the lands between the Foyle and the Bann rivers. They undertook to build up the towns of Coleraine and Derry (renamed Londonderry) and to spend 20,000 pounds in developing their grant. At the same time, two more counties of Ulster, Antrim and Down, were settled, mainly by people from Scotland. The Ulster settlement was the most successful of the plantations. Its success helped to give the area the Protestant character it has today. The Cromwellian settlement. In the years that followed, the government made other settlements in Carlow, King's County, Leitrim, Longford, and Wexford. Even Old English nobles (descendants of Norman settlers) lost their lands. As a result of these plantations, bitter feelings were aroused, and Roman Catholic landowners became alarmed. Justifiably none felt secure in their lands. |

||

|

|

The

1641 Rebellion. |

||

| Religion was a major cause of discontent. Roman Catholics had enjoyed a certain degree of religious freedom under King James I and Charles I. But they feared that the Puritans under Cromwell, who were coming to power in England, would persecute them. In 1641 with memories of their ruthless suppression by Lord Mountjoy, Sir Arthur Chichester and George Carew, little more than a generation past, the Irish rebelled, and for 10 years war raged throughout the country. The Irish Catholics fought for independence. The Old English joined them, but all through the war they declared that they were loyal to the king and were fighting only for religious freedom. The Protestants were also divided into two groups: those who supported the king and those who supported Cromwell's Parliament. |

||

|

|

The

Confederation of Kilkenny |

||

| In 1642, the leaders of the rebellion formed the Confederation of Kilkenny and appointed Owen Roe O'Neill and Thomas Preston as generals, in order to fund the war in Ireland on 19th March1642 The Adventurers Act was passed in the English parliment the Act invited members of the public to invest £200 for which they would receive 1,000 acres of lands that would be confiscated from rebels in Ireland. O'Neill won a great victory at Benburb, in County Tyrone on 5th June 1646, O'Neill and Preston didn't work well as a team. Three years later on 6th November 1649 O'Neill died at Cloughoughter Castle in Lough Oughter, County Cavan while on his way to join a Royalist army assembled by the Earl of Ormond. Cromwell landed in Dublin on 15th August 1649 with an army of twenty thousand, he sacked Wexford and marched north against Drogheda, took the town, and massacred its people. His ruthlessness struck fear into Irish hearts, and many of the southern and eastern towns surrendered without a struggle. When Cromwell returned to England in 1650, the war was almost over, but the Irish army did not surrender for another two years. After the war, Ireland was in a wretched condition. Its population was halved. Most of its leaders were either dead or living in exile, and about 30,000 of its armed men had left to join the armies of France or Spain. The English government then undertook what it hoped would be the final settlement of Ireland. Irish landowners were ordered to move west of the River Shannon to the province of Connacht before May 1, 1652, on pain of death. (Giving rise to the phrase to 'Hell or Connaught.' attributed to Cromwell.) The provinces of Ulster, Leinster, and Munster were divided among Cromwellian soldiers and adventurers (Englishmen who had subscribed money to pay for Cromwell's campaign in Ireland, see The Adventurers Act). Only the Irish landowners were transplanted. The poor people were allowed to remain as tenants, trades people, and labourer's. The Cromwellian settlement was not a complete success. Many of the settlers sold their farms and returned home. Others married into Irish families, and their descendants lost their English characteristics. But the settlement did succeed in creating a new landlord class. Before 1641, Roman Catholics owned about three-fifths of the land. By the 1680's, they owned one-fifth. |

||

|

|

The

Williamite War. |

||

| James

II's accession to the English throne in 1685 raised hopes in the Irish

In 1688, the English people deposed James and offered the throne to William of Orange, a Dutch prince who was married to James daughter Mary. James fled to France, returning the following year, to Ireland with French support, in the hope that the Roman Catholics there would help him to recover his throne. The Protestants proclaimed their allegiance to King William III and fortified the towns of Londonderry and Enniskillen against James. The Protestants became even more defiant when they learnt that a parliament, which James had summoned in Dublin, had declared its intention of giving back the lands occupied by the Cromwellian settlers to Roman Catholics. Ireland was unfortunate to have become the theatre of war, for a conflict which was deeply rooted in political power struggles not only in England but Europe also. |

||

See

also The battle

site in Co Meath. |

|

The

Siege of Derry. |

||

| In 1689, James unsuccessfully besieged Derry for three months. In the following year, William landed at Carrickfergus, in Antrim, with a large army. The war was short and decisive. James was defeated at the Boyne and returned to France. The Irish and their French

allies continued the fight, but they were again defeated, at Aughrim,

and driven back to Limerick. Patrick Sarsfield, Earl of Lucan, defended

the town, but when no French help arrived he surrendered. |

||

|

|

Treaty

of Limerick |

||

| On

Oct. 13, 1691, the Treaty of Limerick was signed. Under this all Irish

All who submitted under the Treaty of Limerick were allowed to keep their lands, if they took an oath of allegiance. One clause of the treaty seemed to promise that Roman Catholics would be free to practice their religion. However the English did feel predisposed to honour the terms of the treaty. |

||

|

|

The

Penal Laws |

||

| (1691-1801) Immediately following the Williamite

War, the Known as the Penal Laws under them Bishops and members of religious orders were banished. Parish priests were allowed to remain, but no new priests could be ordained. The government expected that Roman Catholicism would die out. Other laws aimed to keep Roman Catholics poor and without power were as follows. When a Roman Catholic landowner died, his estate had to be divided equally among his sons. No Roman Catholic could purchase land or lease land for more than 31 years. A Roman Catholic could not carry arms or own a horse worth more than five pounds. Roman Catholics could not teach in a school or send their children abroad to be educated. No Roman Catholic could sit in Parliament or vote in a parliamentary election. Also, they could not take part in local government, or serve on a jury, hold any government office, or become a lawyer or army officer. The religious laws could not be enforced fully, but the other penal laws were. By the 1770's, Roman Catholics had been disposed to the extent that they held only one-twentieth of the land. A few prospered in trade, but most of them were tenant farmers, paying high rent to their Protestant landlords and tithes to the Protestant state church, or land less labourer's, living in great poverty. As the population grew, competition for land increased. More poor people relied on potatoes alone as their staple diet. The Decline of Irish Culture. After the Irish aristocracy lost their lands, a decline in Gaelic learning set in the poets and chroniclers were reduced to poverty. But Irish was still spoken by poor people particularly in the west and western islands. Though the ruling class and the Protestants in Ulster used English.The Presbyterians of Ulster were allowed to vote in parliamentary elections, and a few of them became Members of Parliament. But they did not have full civil rights, and they had to pay tithes to The Church of Ireland. Thousands of them became discontented and emigrated to America. |

||

|

|

The

Protestant Ascendancy. |

||

| The Protestant land owning class created by the plantations ruled Ireland, but the British government did not allow them complete freedom. Restrictions were put on Irish trade, and only the linen industry was encouraged. The Irish Parliament could only pass laws with the permission of the British government, in 1719, the British Parliament claimed to be able to make laws for Ireland. At first, the Protestant ruling class because of a feeling of insecurity did not protest. But gradually some members of the Irish Parliament, who became known as Patriots, began to resent the restrictions on their power. When in 1775, the American War of Independence broke out, the government withdrew troops from Ireland to serve abroad. The Protestant landlords formed companies of Volunteers to defend the country. The Patriots gained control of the Volunteers, and, with their help, Henry Grattan was able to force the British government to remove the restrictions on Irish trade and on the Irish Parliament |

||

|

|

Independent

Parliament in Ireland. |

||

| In 1782, the Irish Parliament began a period of independence which was to last for only 18 years . These were prosperous years for Ireland. Industry was expanding, and there was a demand in Britain for Irish wheat, beef, and butter. Parliament tried to increase prosperity by giving bounties and subsidies. But the majority of the Irish people had little share in this prosperity. The Irish Parliament was still corrupt. The lord lieutenant of Ireland was able to control its decisions by distributing titles, posts, and pensions among its members, it was also unrepresentative. By this time most of the penal laws had been repealed, Roman Catholics got the vote in 1793, but they could not become Members of Parliament, Grattan tried to get Parliament to reform. |

||

|

|

The

United Irishmen. |

||

| See events leading up to 1798 The Presbyterians in Ulster who had been disqualified from holding office, desired a general emancipation including that of the Roman Catholics. They saw America gain its independence from Britain with the American War of Independence, and were inspired to strive for an independent Ireland. In 1778 the Irish parliament, under the influence of the reformist leader Henry Grattan, passed the Relief Act, removing some of the most oppressive disabilities. Meanwhile Irish Protestants, under the pretext of defending the country from the French, who had entered into an alliance with the Americans, had formed military associations of volunteers, with 80,000 members. Backed by this force they demanded legislative independence for Ireland, and as a result of Grattan’s tireless campaigning the British parliament repealed Poynings’ Law and much of the anti-Catholic legislation. Although suffrage was restored to Roman Catholics in 1793, the Irish parliament remained composed entirely of the Protestants of the established Church. After the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, a radical movement began to advocate more extreme reforms. It was particularly strong among the Presbyterians of Ulster. In 1791, a young Dublin lawyer, Theobald Wolfe Tone, founded the Society of United Irishmen. The United Irishmen wanted to unite Irish people of all religious beliefs and to make Parliament representative of all the people. Later, they decided to establish an Irish republic with French help. The French attempted a landing in Bantry Bay in 1796 On the 22nd August 1798 a French force of one thousand men, commanded by general Joseph Humbert landed at Killala Bay in County Mayo. They are reputed to have distributed fifty five thousand muskets to the local population. Together they marched to Castlebar where they defeated General Lake. This became known as the "Races of Castlebar." However victory eluded them on 8th September when they met Lord Cornwallis and his army at Ballinamuck County Longford. After the battle of Ballinamuck, Humbert's "Mayo Legion Flag" came into the possession of John Browne, Lord Altmount, it can be seen at Westport House County Mayo. |

||

|

|

The

Act of Union.

(1801) |

||

| The British government decided to resolve problems in Ireland by uniting the two kingdoms. To persuade the Irish Parliament to pass the Act of Union in 1800, William Pitt promised that Britain would grant political rights to Roman Catholics. The first time the act went to the vote it was defeated by five votes, Cornwallis the Lord Lieutenant and his chief secretary Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh set themselves to reverse the decision. New peerages were promised, pensions and ecclesiastical preferment were granted lavishly; the propitiators of boroughs threatened with disfranchisement were assured compensation for their losses; antiunion members were persuaded to vacate their seats.In all some £1,250,000 was expended on what can only be adequately describes as bribery and corruption When the Act of Union was presented again to the Irish house of commons in January 1800 it was passed by a majority of forty three. The union took effect in 1801. The Act of Union was a disappoint for most of the Irish. Pitt's promise was not honoured, and political union did not bring economic prosperity. As the population grew, more people needed land. But the end of the Napoleonic Wars caused unemployment and made farming unprofitable. Irish industries were not able to compete with the more efficient British ones. The only part of Ireland to benefit from the union was Ulster, where the linen industry expanded and new industries grew up and prospered, based on coal and iron from Britain. Because of this the Protestants became convinced that their prosperity depended on the union with Britain. |

||

|

|

Daniel

O'Connell. |

||

| O'Connell

was a Roman Catholic lawyer, he believed that the country's problems would

not receive adequate attention until Roman Catholics were allowed to sit

in Parliament, Initially, O'Connell had the support of a group of young men called the Young Irelander's. In 1842, three of them, Thomas Davis, John Blake Dillon, and Charles Gavan Duffy, founded a newspaper, called The Nation, to awaken interest in Irish history and culture. They tried to win Protestant support, but most Protestants opposed them. They gradually came to believe in the use of force, and in 1848 a group led by William Smith O'Brien tried to raise a rebellion. They failed, and the government transported their leaders to Tasmania. |

||

|

|

The

Famine. |

||

| By

1801, the population of Ireland was about 5 million. Forty years later

in 1841 the census revealed a population of 8,175,124. (See census

page.) As the population grew, farms were subdivided and dwindled in size.

Many Charles Treveleyan permanent Head of Treasury

under Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, introduced relief schemes in the

poorest areas to enable people to earn enough money to buy maize that

the government imported from the United States. Maize is a grain which

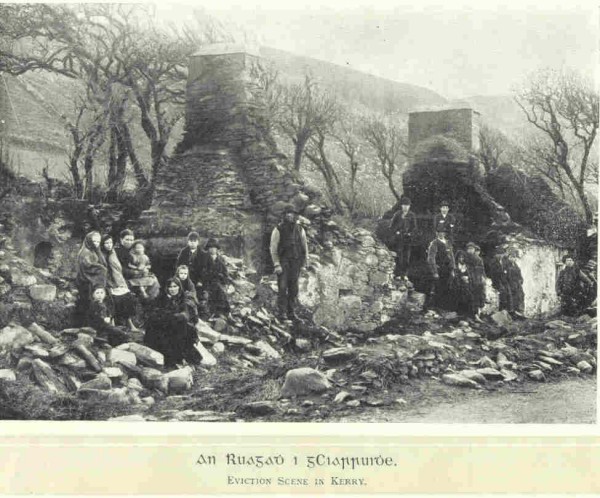

During the winter of 1847-8 it is estimated that £17,000,000 worth of grain, cattle, pigs, flour, poultry and eggs were exported to England, much of this may have been transshipped to England's other overseas colonies. Also no relief from other countries was allowed into Ireland unless it were carried in an English ship, the Nation newspaper dubbed this "British Commercial Christianity" During this period tenants had no means with which to raise their rents which were due twice yearly on 'Gale Day' Many landlords, particularly the absentee ones had their tenants evicted and their houses demolished, leaving them with neither food nor shelter. Josephine Butler an Englishwoman living in Ireland at the time wrote. "Sick and aged, little children, and woman with child were alike thrust forth into the snows of winter. And to prevent their return their cabins were leveled to the ground. The few remaining tenants were forbidden to receive the outcasts, the majority rendered penniless by the famine, wandering aimlessly about the roads or bogs till they found refuge in the workhouse or grave." As a result of the Great Famine, the population

of the country dropped from 81/4 million to 61/2 million. It is believed

that a million people died of hunger and disease. And nearly a million

more Many The famine is Irish artists have produced many images from the famine period, one particularly beautiful example displayed above is entitled Emigrant Ship in Dublin Bay Sunset, by Edward Hayes, click on the image for a larger view. See also the famine of 1741 and Life on an Irish Farm) Ireland also suffered famine in 1315-16 partly as a result of the Bruce invasion and a famine which took hold in Europe at the same time. In 2007 tests crops of potatoes genetically modified to resist blight are to be grown. |

||

|

|

The

Fenian Brotherhood. |

||

| On St Patrick's day 1858, exiles in the United States led by John O'Mahony formed the Fenian Brotherhood, a secret, oath-bound society that aimed to establish an independent non-sectarian Irish republic, if necessary by force. At the same time, James Stephens founded a organization in Dublin, called the Irish Republican Brotherhood. The two movements soon merged. At the end of the American Civil War, some disbanded soldiers joined the Fenian's and other members were recruited from the British army. The Fenian's smuggled ammunition into Ireland and made plans for a rising. But spies kept the government informed of their preparations and, in 1865, most of the leaders were arrested. An uprising took place in 1867, but it was soon suppressed. The Fenian movement failed, but, together with the Great Famine and the activities of Irish agrarian societies that terrorized landlords, it drew the attention of British statesmen to the need for reforms in Ireland. |

||

|

|

Home

Rule. |

||

| William E. Gladstone, who became Prime Minister in 1868, was greatly influenced by these outbreaks of violence in Ireland. At first, he tried to pacify the country by passing a Land Act that gave tenants some security of tenure and by disestablishing the Church of Ireland that is, abolishing its connection with the state. But the Irish were not satisfied and, in 1870, Isaac Butt, a Protestant lawyer, founded the Home Rule movement. It aimed to establish a subordinate parliament in Dublin to deal with purely Irish affairs, leaving such matters as defense and foreign policy to the British government. Butt was a poor leader, and the movement made little progress until 1878, when a young Protestant landlord, Charles Stewart Parnell, took control. |

||

|

|

The

Irish Parliamentary Party. |

||

| Parnell's followers were reunited under John Redmond in 1900, this Irish Parliamentary Party had the support of most of the Irish people. It hoped that the Liberal Party would give Ireland home rule. In 1906, the Liberal Party returned to power. In 1911, it passed a Parliament Act, limiting the powers of the House of Lords, so that a bill would become law if passed by the House of Commons in three successive sessions. In 1912, a third Home Rule Bill was passed by the House of Commons. Though rejected by the House of Lords, it became law in 1914. By this time, new Irish nationalist movements had been founded. |

||

|

|

The

Gaelic League. |

||

| In 1893, Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill founded the Gaelic League to preserve and extend the use of the Irish language. The organization was not political, but many of the young men who joined it became ardent nationalists. In the early 1900's, James Connolly organized the Irish trade union movement. His aim was a socialist republic. During labour troubles in Dublin in 1913, workers formed the Citizen Army, Connolly led it in the 1916 insurrection. |

||

|

|

Sinn

Fein. |

||

| A Dublin journalist Arthur Griffith started a weekly newspaper in 1899, called The United Irishman, in which he advocated the people of Ireland should be more self-reliant. He wanted the Irish members of Parliament to stop attending the House of Commons and to set up a council of three hundred in Ireland. He intended this council to take over as much of the government as possible. Griffith was not a republican. His aim was to restore the constitution of 1782. In 1905, Griffith founded a party called Sinn Fein (we ourselves) to propagate his views, but at first it had little success. He did not believe in the use of force to achieve political aims, but many of his followers did. The Protestants of Ulster were determined to resist home rule. They chose a dynamic leader, Sir Edward Carson, and formed a provisional government to rule Ulster in the event of the Home Rule Bill becoming law. They formed the Ulster Volunteer Force and imported arms from Germany, in case the British government insisted on the measure. Radical nationalists in the south followed Ulster's example and formed the Irish Volunteers. They also imported arms. In 1914, World War I broke out, and it was agreed that the start of home rule should be postponed until the war was over. Most of the southern Volunteers followed the example of John Redmond and supported Britain in the war. |

||

|

|

The

Easter Rising. |

||

| The

rest of the Volunteers passed under the control of the Irish Republican

Brotherhood, who were preparing for rebellion. On Good Friday, Casement was arrested shortly after landing in Kerry. MacNeill then heard of the planned rebellion, and tried to stop it. His orders caused confusion among the Volunteers outside the Dublin area. But the rising took place on Easter Monday. The Volunteers hoisted the Republican flag over the General Post Office in Dublin, and Pearse read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. British troops crushed the rebellion in one week. Fifteen of the leaders were shot. Roger Casement was executed in London. One of the commandants, Eamon de Valera, was sentenced to death, but was later reprieved. The War of Independence. At the outset the rising had little support, but the execution of the leaders caused the people to turn to Sinn Fein. In 1917, Sinn Fein declared itself in favour of an Irish republic. At the general election in the following year, Sinn Fein won 73 parliamentary seats. The Irish Parliamentary Party held only 6 seats. The Sinn Fein members assembled in Dublin on Jan. 21, 1919, and formed a parliament, which they called Dail Eireann. The Dail reaffirmed the republic that had been declared on Easter Monday and elected de Valera as its president. The Volunteers became the Irish Republican Army. The Dail authorized the army to wage war on British troops in Ireland. In 1920, the British government under David Lloyd George passed the Government of Ireland Act, dividing the country into two areas, one consisting of 6 north eastern counties, the other of the remaining 26 counties. Dail Eireann refused to accept the act, and Lloyd George sent over a large force of auxiliary police, recruited from former soldiers, to enforce it. This force became known as Black and Tans. He sent over another force, recruited from former officers, who became known as Auxiliaries. Almost two years of bitter guerrilla warfare followed, until July 11, 1921, when a truce was declared. Arthur Griffith, Michael Collins, Eamon Duggan, Robert Barton, and George Gavan Duffy were sent to London to negotiate a settlement. On Dec. 6, 1921, a treaty was signed. The 26 counties were constituted the Irish Free State and given the status of a dominion. A governor general was to represent the British sovereign in Dublin. The members of Dail Eireann were to take an oath of allegiance to the Crown. The British Navy was to retain control of some Irish ports. The treaty caused a split in the Sinn Fein party, and Dail Eireann ratified it by only 64 votes to 57. The treaty was ratified by Dail Eire on the on Jan. 7, 1922, de Valera resigned as president and Arthur Griffith succeeded him. A week later, a provisional government was established, under the leadership of Michael Collins, to take over authority from the British, peace again eluded Ireland. The disagreement between the Free Staters, who supported the treaty, and the Republicans, who opposed it, was so great that efforts to reach an agreement failed. The country drifted into disorder, and in June 1922, a civil war began. The civil war cost many lives and was a tragic end to the struggle for freedom, Arthur Griffith died, shortly after the war began, worn out by overwork and anxiety, Michael Collins was killed in an ambush near Brandon in his native County Cork on 22nd August 1922. Many of the leaders on the Republican side, including Erskine Childers and Cathal Brugha, also lost their lives. The war went on until April 1923, when de Valera ordered his followers to stop fighting. The Irish Free State was established on Dec. 6, 1922, and a government had been formed under William T. Cosgrave. De Valera and his followers took no part in these proceedings. They did not take their seats in the Dail, because they were not prepared to take the Oath of Allegiance. In 1926, de Valera resigned from Sinn Fein and formed a new party called Fianna Fail. He announced that he and his party intended to enter the Dail, and indicated that he regarded the oath as "an empty formula." The government party called itself Cumann na nGaedheal (later Fine Gael). The Fianna Fail Party won the general election in 1932, and de Valera became president of the executive council. The new government abolished the Oath of Allegiance and severed the links that bound the Irish Free State and Britain. It forbade appeals from Irish courts to the British Privy Council. It passed an Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act and, in 1936, by the External Relations Act, removed the sovereign from the Constitution except for diplomatic purposes. On Dec. 29, 1937, a new Constitution was introduced, which described Ireland as "a sovereign, independent, democratic state," with the name Eire. The head of the state was to be a president, and the Prime Minister was to be called An Taoiseach. The Constitution was accepted by the people in a referendum. In 1938, the British government restored the Irish ports that were held under the Treaty of 1921. |

||

|

|

The

Republic of Ireland. |

||

| In 1948, a coalition government under the Fine Gael leader John A. Costello repealed the External Relations Act, severing the only remaining link between Britain and Eire. The Republic of Ireland was formally declared on April 18, 1949, bringing with it international recognition. The majority of people and all the political parties in the Republic supported the reunification of the country by peaceful means. But the Irish Republican Army has tried to end the partition, by launching guerrilla attacks in Northern Ireland from time to time since the 1930's. Between 1926 and 1960, the number of people employed in industry increased by 112,000. But, in the same period, due mainly to the mechanization of agriculture and changing farming practices, the number of people working on the land dropped by 250,000. Enough jobs could not be created for these people, and thousands of Irish workers were forced to emigrate, mainly to the United Kingdom and the United States. From the late 1950's onward, economic conditions improved slowly, with the result that the annual rate of emigration decreased steadily. Agriculture had always been the main industry in Ireland. Successive governments have tried to create a more balanced economy by the growth of new industries and by introducing tariffs to protect Irish manufacturers. They formed state sponsored companies and boards such as the I D A (Industrial Development Authority) to encouraged businesses from other countries to establish new industries in Ireland. |

||

|

|

| During the late 1960's, through to the 1980's, the Provisional IRA and several offshoot organizations such as the INLA (Irish National Liberation Army) engaged in guerrilla activities in Northern Ireland aimed at a united Ireland. These operations were financed partly by fundraising activities mainly in the USA and the proceeds of criminal activities such as bank robberies, protection rackets, and smuggling, these activities were engaged in by loyalist paramilitaries also, it is said by some that the two sides colluded in Belfast regarding protection rackets. A considerable amount of related violence occurred in the Republic during this period, a number of bank robberies occurred, being mostly attributed to Provisional IRA. Loyalist bombings occurred in Monaghan, Clones, Ballyshannon and Dublin these claimed many lives. Since 1869 fourteen members of The Garda Siochana (Irish police) have lost their lives, not all it must be said can be attributed political activities. On Jan. 1, 1973, the Republic of Ireland joined the European Community this heralded the beginning of a period of unprecedented economic growth, which continues to this day. In 1985, the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom signed an agreement that established an advisory council for Northern Ireland. The council gave the Republic an advisory role, but no direct powers, in the government of Northern Ireland. The Anglo-Irish Agreement was eventually widely accepted by all parties in the Republic, but was bitterly opposed by Unionists in Northern Ireland. Also in 1985, a new political party, the Progressive Democrats, was formed in Ireland. In elections of 1987 and 1989 Fianna Fail party won most seats in the Dail but failed to gain a majority. Charles Haughey, leader of the party, became prime minister of a coalition government formed by Fianna Fail and the Progressive Democrats. Haughey became embroiled in a political scandal and resigned in 1992 Albert Reynolds then became party leader and prime minister. The coalition of Fianna Fail and the Progressive Democrats collapsed later that year, and Reynolds called an election. Fianna Fail and Fine Gael both lost much support. The Labour Party doubled its number of seats, and the Progressive Democrats gained four. In 1993 Fianna Fail and the Labour Party formed a coalition government with Albert Reynolds as prime minister. Reynolds' worked tirelessly toward peace in Northern Ireland. In 1993, he and UK Prime Minister John Major signed the Downing Street Declaration an agreement setting out terms for peace in the province. In 1994, Reynolds resigned over controversy surrounding his appointment of a High Court president. Reynolds was replaced by Fine Gael leader John Bruton at the head of a coalition with Labour. Fianna Fail formed a minority coalition government with the Progressive Democrats in 1997, with Fianna Fail leader Bertie Ahern as prime minister. From 1990 to 1997, Mary Robinson, a Dublin lawyer, served as Ireland's first female president. Mary McAleese, a law professor from Belfast, succeeded Robinson in 1997. McAleese became the first person from Northern Ireland to become president of Ireland. She later became embroiled in controversy when in a speech she referred to northern Protestants as nazis. |

||

|

|

| In 1998 a peace plan was accepted by all sides December 2004 a bank official of the Northern Bank in Belfast was kidnapped together with members of his family there followed a robbery, the largest in Irish history, republicans were blamed. In an effort to avoid the robbers spending the money the bank recalled all its currency and issued new notes. |

||

|

|

| In October 2006 several business premises were destroyed in Belfast by fire bombs, this was attributed to dissident republicans. Later in the year the Sein Fein leadership claimed their lives were under threat from the dissidents, who also were reputed to hold a list of serving and former members of the security forces who were to be targeted. Although all the political parties claimed the troubles were at an end, the legacy lived on particularly in ghetto areas, such as east and west Belfast, Londonderry and south Armagh. In these areas the rule of law was many claimed, not applied to its fullest extent, mainly through intimidation, not only of witnesses but of people who's job entailed assisting in applying the law, such as bailiffs and those assisting them. The police were seen as unable, or perhaps unwilling to tackle the intimidation, fearful of alienating the communities. |

||

|

|

successive

group, providing the opportunity for the next invaders who were

usually better armed and more experienced in warfare, to gain

a foothold. This lack of cohesiveness and tendency towards personal

material enhancement appears to have been the ultimate downfall

of almost all of Irelands invaders, as they fought among themselves,

and with previously arrived groups to control the land.

successive

group, providing the opportunity for the next invaders who were

usually better armed and more experienced in warfare, to gain

a foothold. This lack of cohesiveness and tendency towards personal

material enhancement appears to have been the ultimate downfall

of almost all of Irelands invaders, as they fought among themselves,

and with previously arrived groups to control the land.  Irish

nation of today is descended from a rich cultural and genealogical mixture

of all these peoples, who came conquered and in the fullness of time integrated,

giving rise to the phrase 'More Irish than the Irish themselves.'

Irish

nation of today is descended from a rich cultural and genealogical mixture

of all these peoples, who came conquered and in the fullness of time integrated,

giving rise to the phrase 'More Irish than the Irish themselves.' of Ireland, were probably Ulster,

Leinster, Munster, Connaught, and Mide. But the number of provinces and

their boundaries were in a state of constant flux. According to tradition,

King Cormac mac Airt built a splendid palace at Tara, in County Meath,

forming the new kingdom of Meath, and called himself Árd Ri (high

king). Though he was never the ruler of whole of Ireland, his descendants

claimed that he founded the high kingship of Tara.

of Ireland, were probably Ulster,

Leinster, Munster, Connaught, and Mide. But the number of provinces and

their boundaries were in a state of constant flux. According to tradition,

King Cormac mac Airt built a splendid palace at Tara, in County Meath,

forming the new kingdom of Meath, and called himself Árd Ri (high

king). Though he was never the ruler of whole of Ireland, his descendants

claimed that he founded the high kingship of Tara.

missionaries to leave Ireland, although it could be said there were

missionaries to leave Ireland, although it could be said there were  of

this period was specially made for them. Examples of such metalwork are

the

of

this period was specially made for them. Examples of such metalwork are

the  with a large army, and won a decisive victory

at Hastings.

with a large army, and won a decisive victory

at Hastings.

of England (Son of Henry II) landed in Waterford with 300

Knights and a large number of men at arms, intent on curbing the power

of his Barons. Upon his arrival the Irish chief in the area came to

welcome and pay homage to him, .John appears to have derided his Irish

subjects, it is said that their beards were rudely pulled in reticule,

by the clean shaven members of John's retinue. The ever proud and sensitive

Irish withdrew and took their grievance's to the Kings in the west and

south of Ireland, with the result that John's visit to Ireland was a

disastrous failure and he returned to England on 17th December.

of England (Son of Henry II) landed in Waterford with 300

Knights and a large number of men at arms, intent on curbing the power

of his Barons. Upon his arrival the Irish chief in the area came to

welcome and pay homage to him, .John appears to have derided his Irish

subjects, it is said that their beards were rudely pulled in reticule,

by the clean shaven members of John's retinue. The ever proud and sensitive

Irish withdrew and took their grievance's to the Kings in the west and

south of Ireland, with the result that John's visit to Ireland was a

disastrous failure and he returned to England on 17th December.

,

so possibly he had designs on an independent Kingdom, which King John

had no intention of allowing.

,

so possibly he had designs on an independent Kingdom, which King John

had no intention of allowing. he was joined by Justiciar, John de Gray, bishop of Norwich and a body

of Irish troops. One of the reasons that King John came to Ireland (was

to suppress the power of the lord of Breton, William de Breos, Hugh

de Lacy's father in-law).Because after the battle of Mireabeau in 1102

and the capture of his nephew Arthur of Brittany , who as the son of

his brother Geoffrey was the only other claimant to the English throne.

After the battle Arthur had been placed in the custody of de Breos,

and after his disappearance there was much speculation about his death,

many believed at the hands of King John personally; as de Breos, who

knew the truth about Arthurs disappearance and had used this to overreached

himself in the kings eyes, leading John to curtail his power.

he was joined by Justiciar, John de Gray, bishop of Norwich and a body

of Irish troops. One of the reasons that King John came to Ireland (was

to suppress the power of the lord of Breton, William de Breos, Hugh

de Lacy's father in-law).Because after the battle of Mireabeau in 1102

and the capture of his nephew Arthur of Brittany , who as the son of

his brother Geoffrey was the only other claimant to the English throne.

After the battle Arthur had been placed in the custody of de Breos,

and after his disappearance there was much speculation about his death,

many believed at the hands of King John personally; as de Breos, who

knew the truth about Arthurs disappearance and had used this to overreached

himself in the kings eyes, leading John to curtail his power.  Robert Bruce king

of Scotland and his brother Edward at the battle of Bannochburn. Thereby

gaining their long fought for independence from England. Upon learning

of the Bruce victory, O'Neill of Tyrone (Brother in law of Robert)

invited the Bruce's to Ireland, offering to make Edward King of Ireland.

Robert Bruce king

of Scotland and his brother Edward at the battle of Bannochburn. Thereby

gaining their long fought for independence from England. Upon learning

of the Bruce victory, O'Neill of Tyrone (Brother in law of Robert)

invited the Bruce's to Ireland, offering to make Edward King of Ireland.

arrangement. Believing that the best

way to subdue Ireland was to introduce colonies of English people into

the country. In 1556, she confiscated the territory of the O'Mores and

O'Connor's in Laois and Offaly and sent English settlers there. The

settlers were to take to Ireland with them English tenants and servants.

They were also to build stone houses, and to provide the Crown with

a certain number of troops when required. In honour of the queen and

her husband, the king of Spain, the area was made into shires and these

were called Queen's County and King's County. But the plantation was

not successful.

arrangement. Believing that the best

way to subdue Ireland was to introduce colonies of English people into

the country. In 1556, she confiscated the territory of the O'Mores and

O'Connor's in Laois and Offaly and sent English settlers there. The

settlers were to take to Ireland with them English tenants and servants.

They were also to build stone houses, and to provide the Crown with

a certain number of troops when required. In honour of the queen and

her husband, the king of Spain, the area was made into shires and these

were called Queen's County and King's County. But the plantation was

not successful.  who succeeded her in 1558, was

at first tolerant in her dealings with Roman Catholics. But, from about

1575 onwards, she adopted a harsher attitude, and a number of Irish

bishops and priests were executed. This persecution drove the Irish

and those of the Anglo-Irish who had remained Roman Catholics closer

together. A new national spirit developed that was both Roman Catholic

and anti-English in outlook.

who succeeded her in 1558, was

at first tolerant in her dealings with Roman Catholics. But, from about

1575 onwards, she adopted a harsher attitude, and a number of Irish

bishops and priests were executed. This persecution drove the Irish

and those of the Anglo-Irish who had remained Roman Catholics closer

together. A new national spirit developed that was both Roman Catholic

and anti-English in outlook.

Catholics

that he would allow them to recover their lands. James a Roman Catholic,

appointed Richard Talbot a Catholic, as lord deputy, and made him Earl

of Tyrconnell instructing him to give Roman Catholics a fairer share of

political power in Ireland. Talbot carried out the king's instructions

and also built up a large Roman Catholic army.

Catholics

that he would allow them to recover their lands. James a Roman Catholic,

appointed Richard Talbot a Catholic, as lord deputy, and made him Earl

of Tyrconnell instructing him to give Roman Catholics a fairer share of

political power in Ireland. Talbot carried out the king's instructions

and also built up a large Roman Catholic army.

soldiers

who wanted to leave the country were allowed to do so, several thousand

of them accompanied Sarsfield to France. Many of them became mercenary's

and later distinguished them selves on the battlefields of Europe

soldiers

who wanted to leave the country were allowed to do so, several thousand

of them accompanied Sarsfield to France. Many of them became mercenary's

and later distinguished them selves on the battlefields of Europe

government

confiscated another 405,000 hectares of land. By 1704, Roman Catholics

owned no more than one-seventh of the land. Even this amount was later

reduced by the operation of the extremely harsh religious laws that were

passed between 1692 and 1727 these laws were in violation of the

government

confiscated another 405,000 hectares of land. By 1704, Roman Catholics

owned no more than one-seventh of the land. Even this amount was later

reduced by the operation of the extremely harsh religious laws that were

passed between 1692 and 1727 these laws were in violation of the  and

until Ireland had a parliament of its own. In 1823, he formed the Catholic

Association, to work for full political rights for Roman Catholics. All

of the Irish people, except the Protestants of Ulster, backed him. In

1828,

and

until Ireland had a parliament of its own. In 1823, he formed the Catholic

Association, to work for full political rights for Roman Catholics. All

of the Irish people, except the Protestants of Ulster, backed him. In

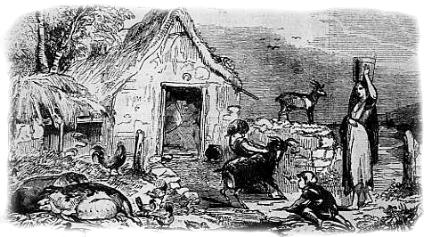

1828,  farming families

lived on potatoes and little else. In 1845, blight affected the potato

crop in widely separated areas. The following year it appeared throughout

the whole country. The potatoes rotted in the ground, throughout the country

the air was filled with the stench of the rotting tubers, and many people

faced starvation.

farming families

lived on potatoes and little else. In 1845, blight affected the potato

crop in widely separated areas. The following year it appeared throughout

the whole country. The potatoes rotted in the ground, throughout the country

the air was filled with the stench of the rotting tubers, and many people

faced starvation.

needs

to be ground exceptionally finely to deliver its nutritional value, the

Irish did not have the means to do this, the coarsely ground maize passing

through their systems largely undigested. These measures proved to be

totally inadequate, and the next government, under Lord John Russell,

had to distribute food free of charge. But these relief measures were

also inadequate. Hundreds of thousands died, along the roadsides or in

their huts, where sometimes entire families lay unburied, their corpses

gnawed upon by stray dogs and rats. In a hovel in County Mayo a old woman

was found barely alive with parts of the arms and face eaten off by rats,

she died shortly after.

needs

to be ground exceptionally finely to deliver its nutritional value, the

Irish did not have the means to do this, the coarsely ground maize passing

through their systems largely undigested. These measures proved to be

totally inadequate, and the next government, under Lord John Russell,

had to distribute food free of charge. But these relief measures were

also inadequate. Hundreds of thousands died, along the roadsides or in

their huts, where sometimes entire families lay unburied, their corpses

gnawed upon by stray dogs and rats. In a hovel in County Mayo a old woman

was found barely alive with parts of the arms and face eaten off by rats,

she died shortly after. emigrated,

most of them to the United States and Canada. They left Ireland with bitterness

in their hearts, believing that Britain was the cause of all their suffering.

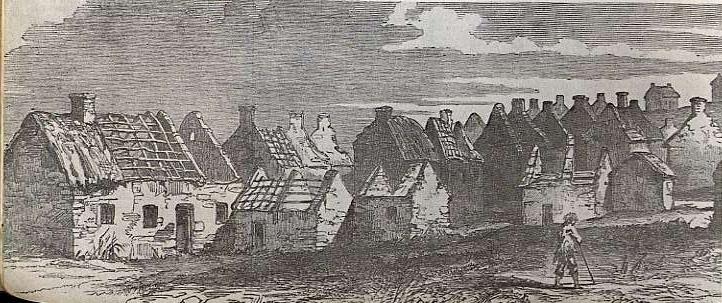

The poignant drawing on the left depicts a deserted village in the west

of Ireland, scenes like this were common in post famine Ireland.

emigrated,

most of them to the United States and Canada. They left Ireland with bitterness

in their hearts, believing that Britain was the cause of all their suffering.

The poignant drawing on the left depicts a deserted village in the west

of Ireland, scenes like this were common in post famine Ireland.

The leaders of the group Thomas Clarke,

The leaders of the group Thomas Clarke,