A Smaller Social History of Ancient IrelandBy P W Joyce 1906 |

|

CHAPTER III. |

||

| ; | WARFARE. Military Formation and Marching In going to battle the Irish often rushed pell-mell in a crowd without any order. But they sometimes adopted a more scientific plan, advancing in regular formation, shoulder to shoulder, forming a solid front with shields and spears. On the morning of the day of battle each man usually put as much food in a wallet that hung by his side as was sufficient for the day. When a commander had reason to suspect the loyalty or courage of any of his men in a coming battle, he sometimes adopted a curious plan to prevent desertion or flight off the field. He fettered them securely in pairs, leg to leg, leaving them free in all other respects. Horse and Foot.--Cavalry did not form an important feature of the ancient Irish military system: we do not find cavalry mentioned at all in the Battle of Clontarf, either as used by the Irish or Danes. But kings kept in their service small bodies of horse-soldiers, commonly called in Irish "horse-host." The chief men, too, often rode in battle, and the leaders fought on horseback. After the Anglo-Norman Invasion cavalry came into general use. Each horseman had at least one footman to attend him--called a gilla or dalteen--armed only with a dart or javelin. In later times each horseman had two and sometimes three attendants.

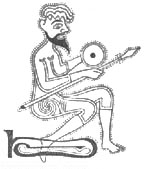

FIG. 28. Foot-soldier preparing to receive charge. One of several grotesque

figures in the illustrations of the Book of Kells (seventh or eighth century).

This shows that when receiving a charge, the Irish soldiers--sometimes

at least--went on one knee. (From Wilde's Catalogue). Two kinds of foot-soldiers are often mentioned in Irish records, the kern and galloglasses. The kern were light-armed soldiers: they wore headpieces, and fought with a skian (a dagger or short sword) and with a javelin. The galloglasses appear only in later times--after the Anglo-Norman Invasion. They are not met with in ancient Irish writings. They were heavy-armed infantry, wearing a coat of mail and an iron helmet, with a long sword by the side, and carrying in the hand a broad, heavy, keen-edged axe. They are usually described as large-limbed, tall, and fierce-looking. It is almost certain that the galloglasses, and the mode of equipping them, were imitated from the English.

FIG. 29. Two of the eight galloglasses on King Felim O'Conor's tomb in

Roscommon Abbey (thirteenth century). (From Kilkenny Archaeological Journal).

War-Cries.--The armies charged with a great shout called barrán-glaed [barran glay], 'warrior-shout'--a custom which continued until late times. The different tubes and clans had also special war-cries; and the Anglo-Normans fell in with this custom, as they did with many others. The war cry of the O'Neills was Lamh-derg aboo, i.e. 'the Red hand to victory' (lamh, pron. lauv, 'a hand'), from the figure of a bloody hand on their crest or cognisance: that of the O'Briens and Mac Carthys, Lamh-laidir aboo, 'the Strong-hand to victory' (laidir, pron. lauder, 'strong'). The Kildare FitzGeralds took as their cry Crom aboo, from the great Geraldine castle of Crom or Croom in Limerick; the Earl of Desmond, Shanit aboo, from the castle of Shanid in Limerick. The Butlers' cry was Butler aboo. Most of the other chiefs, both native and Anglo-Irish, had their several cries. Martin found this custom among the people of the Hebrides in 1703; and in Ireland war-cries continued in use to our own day. END OF CHAPTER III. |

|