A Smaller Social History of Ancient IrelandBy P W Joyce 1906 |

|

CHAPTER III. |

||

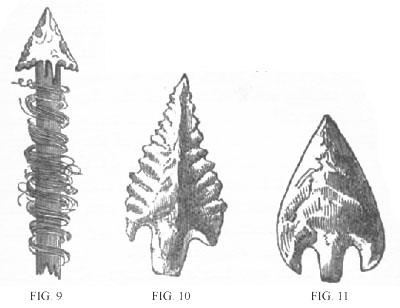

| ; | WARFARE. 3. Arms, Offensive and Defensive. Handstone.--Among the missive weapons of the ancient Irish was the handstone, which was kept ready for use in the hollow of the shield, and flung from the hand when the occasion came for using it. Handstones were specially made, and were believed to possess some sort of malign mystical quality, which rendered them very dangerous to the enemy. The handstone was called by various names, such as cloch, lia, lec, &c. Sling and Sling-stones.--A much more effective instrument for stone-throwing was the sling, which is constantly mentioned in the Tales of the Táin, as well as in Cormac's Glossary and other authorities, in such a way as to show that it formed an important item in the offensive arms of a warrior. The accounts, in the old writings, of the dexterity and fatal precision with which Cuculainn and other heroes flung their sling-stones, remind us of the Scriptural record of the 700 chosen warriors of Gibeah who could fight with left and right hand alike, and who flung their sling-stones with such aim that they could hit even a hair, and not miss by the stone's going on either side (Judges xx. 16). The Irish used two kinds of sling. One, which was called by two names teilm and taball [tellim taval] consisted of two thongs attached to a piece of leather at bottom to hold the stone or other missile: a form of sling which was common all over the world, and which continues to be used by boys to this day. The other was called crann-tabaill, i.e. 'wood-sling' or 'staff-sling,' from crann, 'a tree, a staff, a piece of wood of any kind'; which indicates that the sling so designated was formed of a long staff of wood with one or two thongs--like the slings we read of as used by many other ancient nations. David killed Goliath with a staff-sling. Those who carried a sling kept a supply of round stones, sometimes artificially formed. Numerous sling-stones have been found from time to time--many perfectly round--in raths and crannoges, some the size of a small plum, some as large as an orange, of which many specimens are preserved in museums. Though the Irish had the Bow and Arrow, it was never a favourite weapon with them. They used only the long bow, which was from four to five feet in length, and called fidbac [feevak], signifying 'wood-bend,' from fid, 'wood,' and bac, 'a bend.' FIGS. 9, 10 & 11. Flint arrow-heads. Fig. 9 shows

arrow with a piece of the shaft and the tying gut as it was found. (From

Wilde's Catalogue).

The Mace--The club or mace--known by two names--matan and lorg--though pretty often mentioned, does not appear to have been very generally used. In the Tales, a giant or an unusually strong and mighty champion, is sometimes represented as armed with a mace. There can be no doubt that the mace was used: for in the National Museum in Dublin there are several specimens of bronze mace-heads with projecting spikes. One of them is here represented, which, fixed firmly on the top of a strong lorg or handle, and wielded by a powerful arm, must have been a formidable weapon. FIG. 12. Bronze head of Irish battle-mace, now in the National Museum,

Dublin. The handle was fastened in the socket.

Spear.--The Irish battle-spears were used both for thrusting

and for casting. They were of various shapes and sizes: but all consisted

of a bronze or iron head, fixed on a wooden handle by means of a hollow

cro or socket, into which the end of the handle was thrust and kept

in place by rivets. The manufacture of spear-heads was carried to great

perfection in Ireland at a very early age--long before the Christian

era--and many of those preserved in our museums are extremely graceful

and beautiful in design and perfect in finish: evidently the work of

trained and highly skilled artists. The iron spears were hammered into

shape: those of bronze were cast in moulds, and several specimens of

these moulds may be seen in the National Museum (see chapter xx., section

3, infra). Both bronze and iron spear-heads are mentioned in our oldest

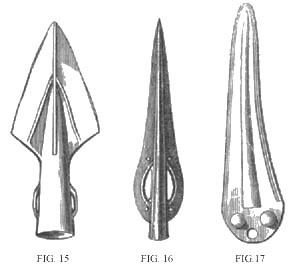

literature. In the National Museum in Dublin there is a collection of several hundred spear-heads of all shapes and sizes, the greater number of bronze, but some of iron, and some of copper; and every other museum in the country has its own collection. They vary in length from 36 inches down. Some of the Irish names for spear-heads designated special shapes, while others were applied to spears of whatever shape or size. The words gae, ga, or gai; faga or foga; and sleg (now written sleagh: pron. sla) were sometimes used as terms for a spear or javelin in general. Among the spears of the Firbolgs was one called fiarlann [feerlann], 'curved blade' (fiar, 'curved'; lann, 'a blade'), of which many specimens are to be seen in the National Museum. The fiarlann was rather a short sword than a spear. In the ancient Irish battle-tales a sharp distinction is made between the spears of the Firbolgs and of the Dedannans respectively: to which O'Curry first drew attention. The Firbolg spears are described as broad and thick, with the top rounded and sharp-edged, and having a thick handle. The spear used by the Dedannans was very different, being long, narrow, and graceful, with a very sharp point. Whether these two colonies are fictitious or not, a large number of spear-heads in the National Museum answer to those descriptions. FIGS. 15, 16, & 17. Fig. 15, a Firbolg spear-head; fig. 16, a Dedannan

one; fig. 17, a Fiarlann. Now in the National Museum, Dublin.

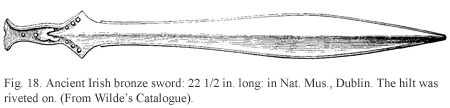

Some of the spears of the heroes of the Red Branch and other great champions are described in the old legends as terrible and mysterious weapons. The spear of Keltar of the Battles, which was called Lón or Luin, twisted and writhed in the hand of the warrior who bore it, striving to make for the victim whose blood was ready for spilling. Some spears were regularly seized with a rage for massacre; and then the bronze head grew red-hot, so that it had to be kept near a caldron of cold water, or, more commonly, of black poisonous liquid, into which it was plunged whenever it blazed up with the murder fit. The Greeks of old had the same notion; and those fearful Irish spears remind us of the spear of Achilles, as mentioned by Homer, which when the infuriated hero flung it at Lycaon, missed the intended victim, and, plunging into the earth, "stood in the ground, hungering for the flesh of men." So also another Greek hero is made to say: "My spear rageth in my hands," with the eagerness to plunge at the Trojans. Sword.--The Irish were fond of adorning their swords elaborately. Those who could afford it had the hilt ornamented with gold and gems. But the most common practice was to set the hilts round with the teeth of large sea-animals, especially those of the seahorse--a custom also common among the Welsh. This practice was noticed by the Roman geographer Solinus in the third century A.D.:--"Those [of the Irish] who cultivate elegance adorn the hilts of their swords with the teeth of great sea-animals."

The usual term for an ordinary sword was cloidem [cleeve]: and one of the largest size was called cloidem-mor, a name which the Scotch retain to this day in the Anglicised form "claymore," which nearly represents the proper sound. Many warriors practised to use the sword with the left hand as well as with the right, so as to be able to alternate, or to fight with one in each hand as occasion required. Some made it a practice to sleep with their favourite sword lying beside them under the bed-clothes. A short sword or dagger was much in use among the Irish, called a scian [skean], literally a 'knife.'

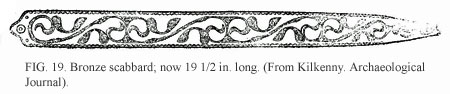

The blade (lann) was kept in a sheath or scabbard. Sometimes the sheath was made of bronze: and several of these are preserved in museums. The beautiful specimen figured on last page was found in a crannoge.

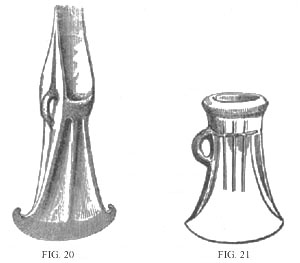

The battle-axe (tuag or tuagh, pron. tooa) has been in use from prehistoric times in Ireland; as is evident from the fact that numerous axe-heads of stone, as well as of bronze, copper and iron, have been found from time to time, and are to be seen in hundreds in the National Museum and elsewhere. These are now commonly called celts, of which the illustrations on last page will give a good idea. FIGS. 20 & 21. Two types of metallic celts or early

battle-axes. (From Wilde's Catalogue).

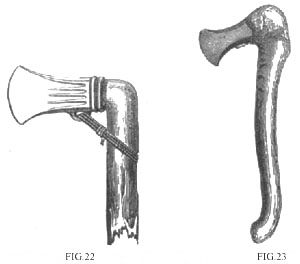

FIGS. 22 & 23. To show how metallic celts or axe-heads

were fastened on handles. Fig. 23 shows one found in its original handle,

as seen in the illustration. It has a loop underneath, which is partly

eaten away by rust. Fig. 22 is a conjectural restoration of the fastening

of this kind of celt. (From Wilde's Catalogue).

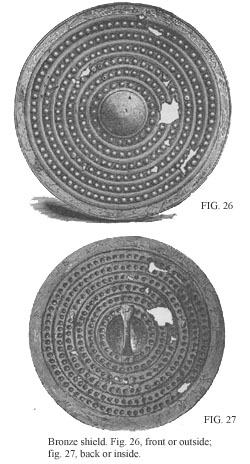

FIG. 25. Two galloglasses depicted on a map of Ireland of 1567: showing the broad battle-axe. One of the two galloglasses in fig. 29 below holds a broad axe. Armour.--We know from the best authorities that at the time of the invasion--i.e., in the twelfth century--the Irish used no metallic armour. Giraldus says:--"They go to battle without armour, consider- ing it a burden, and deeming it brave and honourable to fight without it." The Danes wore armour: and it is not unlikely that the Irish may have begun to imitate them before the twelfth century: but, if so, it was only in rare cases. They never took to it till after the twelfth century, and then only in imitation of the English. But the tales describe another kind of protective covering as worn by Cuculainn, and by others; namely, a primitive corslet made of bull-hide leather stitched with thongs, "for repelling lances and sword-points, and spears, so that they used to fly off from him as if they struck against a stone." Greaves to protect the legs from the knee down were used, and called by the name asán. Helmet.--That the Irish wore a helmet of some kind in battle is certain: but it is not an easy matter to determine the exact shape and material. It was called cathbharr [caffar], i.e., 'battle-top,' or battle-cap, from cath [cah], 'a battle,' and barr, 'the top.' It was probably made of hard tanned leather, possibly chequered with bars of iron or bronze. The warriors often dyed their helmets in colours: and there was commonly a crest on top. Shield.--From the earliest period of history and tradition, and doubtless from times beyond the reach of both, the Irish used shields in battle. The most ancient shields were made of wicker-work, covered with hides: they were oval-shaped, often large enough to cover the whole body, and convex on the outside. It was to this primitive shield that the Irish first applied the word sciath [skeé-a], which afterwards came to be the most general name for a shield of whatever size or material. These wicker shields--of various sizes--continued in use in Ulster even so late as the sixteenth century, and in the Highlands of Scotland till 200 years ago. Shields were ornamented with devices or figures, the design on each being a sort of cognisance of the owner to distinguish him from all others. These designs would appear to have generally consisted of concentric circles, often ornamented with circular rows of projecting studs or bosses, and variously spaced and coloured for different shields. As generally confirming the truth of these accounts, the shields in the Museum have a number of beautifully wrought concentric circles formed either of continuous lines or of rows of studs; as seen in the illustration. Sometimes figures of animals were painted on shields.

Shields were often coloured according to the fancy of the wearer. We read of some as brown, some blood-red; while many were made pure white. This fashion of painting shields in various colours continued in use to the time of Elizabeth. Hide-covered shields were often whitened with lime or chalk, which was allowed to dry and harden, as soldiers now pipeclay their belts. Hence we often find in the Tales such expressions as the following:--"There was an atmosphere of fire from [the clashing of] sword and spear-edge, and a cloud of white dust from the cailc or lime of the shields." The shields in most general use were circular, small, and light, of wickerwork, yew, or more rarely of bronze, from 18 to 20 inches in diameter, as we see by numerous figures of armed men on the high crosses and in manuscripts, all of whom are represented with shields of this size and shape. I do not remember seeing one with the large oval shield. Specimens of both yew and bronze shields have been found, and are now preserved in museums. Shields were cleaned up and brightened before battle. Those that required it were newly coloured, or whitened with a fresh coating of chalk or lime: and the metallic ones were burnished--all done by gillies or pages. The shield, when in use, was held in the left hand by a looped handle or crossbar, or by a strong leather strap, in the centre of the inside, as seen in fig. 27, above. But as an additional precaution it was secured by a long strap, called iris or sciathrach [skiheragh], that went loosely round the neck. When not in use, it was slung over the shoulder by the strap from the neck. In pagan times it was believed that the shield of a king

or of any great commander, when its bearer was dangerously pressed in

battle, uttered a loud melancholy moan which was heard all over Ireland,

and which the shields of other heroes took up and continued. The shield-moan

was further prolonged; for as soon as it was heard, the "Three

Waves of Erin" uttered their loud melancholy roar in response.

(For the Three Waves, see chap. xxvi., sect. 9.) |

|